The Effects Of The Global Economic Crisis And Structural Adjustment On Women And Gender Relations In Greece: First Wave

Association for Women’s Rights in Development

[AWID, 15 April 2011] Growing unemployment, dwindling pensions, increasing taxes, domestic violence and a possible reinforcing of “traditional values” were just a few of the challenges facing women during Greece’s first wave of economic crisis and structural adjustment.

By Lois Woestman and Kathambi Kinoti

In 2009, AWID commissioned research into the impact of the global financial crisis on women’s rights. One of the countries covered in the research was Greece, the first EU country to face the possibility of defaulting on its foreign debts. Lois Woestman, a US and Greek feminist researcher conducted the research which is published by AWID in a brief entitled “The Global Economic Crisis and Gender Relations: The Greek case.”* In this Friday File, we summarize some of the analysis presented in the brief.

Woestman explains that due to a combination of domestic and international dynamics, the economic and financial crises that had been building for some time came to a head in Greece in late 2009. Internally, due to lack of coherent economic strategies Greece’s productive sector had not been strong – and it was weakening as a result of the global economic downturn. This situation had been compounded by public sector mismanagement. Bribery was rampant and the government was highly indebted. By International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates, by end of 2009, Greece’s public debt was approximately 6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which was well above the 3% EU cap for eurozone members. Successive governments had been covering up these growing economic and fiscal crises by issuing falsified data.

When the socialist Pasok party came to power late 2009, it published accurate statistics and, as Woestman argued, set off a domino effect. Greece’s creditworthiness ratings plummeted and financial speculators drove up the price of Greek debt, demanding a greater return on what was sold as risky investment. The Greek government had to pay more to borrow, increasing the debt mountain further.

Imposing structural adjustment measures

Shortly thereafter, the EU and IMF stepped in with a structural adjustment “rescue package,” pressuring Greece to dismantle its welfare system by implementing harsh austerity measures. For several years, successive Greek administrations – conservative and liberal – had resisted implementing structural adjustment measures because of their philosophical commitments to the welfare state, and the fact that they risked being voted out of power if they dismantled it. Promising to inject money into the economy, increase social spending to mitigate the effects of the crisis on lower income groups, crack down on tax evasion, and enhance government transparency, in October 2009, the socialist Pasok party won elections by a landslide. However, by early 2010, the Pasok administration reversed tack, accepted the EU-IMF structural adjustment program, and began introducing harsh austerity measures.

Impact on Greek women and gender relations

This first wave of the economic and fiscal crisis in Greece, and the structural adjustment program put in place to address it, kicked off processes heightening class inequalities and social unrest, gender inequalities and a crisis in the unpaid “care economy”.

Unemployment began rising, with rates for women double those for men. Despite this, men were benefiting disproportionately from government unemployment support measures aimed primarily at sectors in which men predominated, rather than those in which women predominated.

As a result of the crisis, part-time employment rates were increasing by 25% for men and almost 20% for women. While this was a significant rise in the number of men having only part-time employment, women still constituted around three-quarters of part-time employees, and typically had low salaries and limited social benefits. The government public sector hiring freeze, including in health and education in which women predominated slowed down the hiring of women, meaning greater numbers of women without adequate social protection such as maternity benefits.

Wages and pensions were cut in both the public and private sectors. Gender wage gaps existed in both sectors and at 20%, were wider in the private sector. The gaps meant that wage cuts hit women even harder making more women poor.

Due to gender wage gaps and the years many women take out of paid work to care for dependents, Greek women already received smaller pensions than men. Until a recent policy change in the public sector which raised the retirement age to 65 for both women and men, women could opt to retire up to 15 years earlier in order to raise their children. On the whole, Greek women live longer than men. As a result, many – especially women - pensioners will have to look for jobs to supplement their meager retirement benefits.

Some Greeks saw the rise in retirement age as a move fostering gender equality. Others argued that it was impractical and unfair until facilities were set up to reduce women’s unpaid dependent care work burdens which were growing, given cuts in government health and education spending.

As incomes dropped, taxes rose. Value added taxes have risen twice already. These across-the-board taxes hit the poorest hardest, as they disproportionately reduce their already limited spending power. In short, due to a one-sided focus on austerity, but with no growth plan in site, the Greek economy has entered a serious recession with no prospect of recovery in sight.

Poverty is rising as a result. Prior to the economic crisis, Greece already had higher levels of poverty than other eurozone countries. In 2007, 21% of women and 18% of men were classified as poor. Now, many previously middle-income persons are falling into the “new poor” category.

The economic crisis has heightened domestic violence. Men who feel that their masculinity is threatened by unemployment have become increasingly abusive towards women with whom they live and children are experiencing some of the aftermath of their parents’ anxiety.

Dismal career prospects for young people may prompt a return to traditional “family values”. Woestman quotes a Greek psychologist and analyst who says: “If young women in particular feel they have little chance of a meaningful career, they may decide to forfeit it entirely and focus on those things that have most meaning and value - which in the Greek context would likely mean focusing solely on a role as mother and homemaker.”

Proposed alternatives

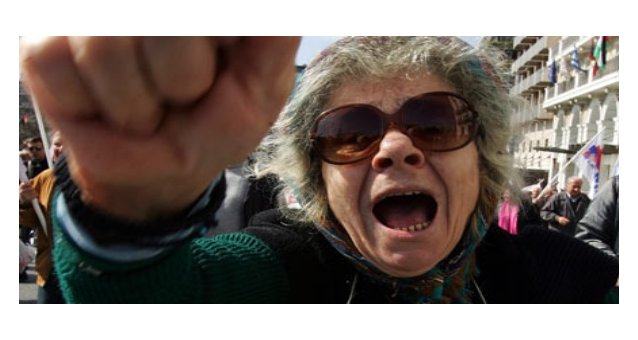

At public demonstrations, Greek protesters have called for corrupt politicians to be prosecuted, and for heavier taxes to be imposed on the wealthy, the main tax evaders. There have also been proposals to sell off state assets, and privatizations have begun. However, most Greeks oppose this, because, as has occurred in countries where similar programmes have been introduced, foreign buyers will siphon profits out of the country. They also see it as a serious loss of national sovereignty.

The Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou has proposed introducing global economic governance measures to “correct many of the excesses of globalization” such as the lack of adequate regulation of derivative transactions. Such measures could include the introduction of a tax on financial transactions.

transform!, a European network for alternative thinking and dialogue, has proposed revising the entire “European project” which they argue has turned into a neoliberal one. The Women in Development Europe (WIDE) Network has proposed a rethinking of how components of “the economy” are defined. According to the Network “economics should focus on provisioning activities that maintain life- human and environmental – thus providing the basis for the radical reworking of development models towards a more human and environmentally sustainable economic system.”

Woestman noted that during those early days of crisis and structural adjustment, there were few specifically feminist alternatives proposed by Greek feminists. The feminist movement in Greece is small and traditionally embedded within party and trade union politics. Feminists in the trade unions have had more resources and space for organizing than those outside the structure, but their organizing has been within the confines of trade union politics – which means gender issues have often been treated as secondary. Woestman interviewed a Greek feminist who said that despite the higher unemployment rate rise for women, since men are losing jobs too, many women do not think that it is strategic to highlight “women’s issues” at this time.

However, as Woestman noted, where traditional party politics appears to have disappointed the great majority of Greeks, this provided opportunities for a stronger independent feminist movement and urgency for its action on many fronts.

Amongst these urgent issues is dependent care. The Greek government should increase, not cut, dependent care services – not least due to changes in pension ages, which no longer enable older women to take on this work unpaid. The government already had a plan to use EU funds to subsidize private day care facilities, but trade union feminists emphasized that it would be better to use the funds to create new public facilities. Unpaid dependent care work should also be recognized in the pension system so that women taking off years for dependent care are not disadvantaged at retirement. This would help reverse the trend of fiscal crisis being passed from the state to households – and particularly to women.

Feminists and others also argue that budget cuts can be made in other places instead of in social spending. Due to the long-standing tensions with Turkey, as compared to other EU countries, Greece spends a disproportionate amount of its GDP on military spending. Greek feminists and others have argued that this should be reduced in favor of social spending. The Greek government has proposed to Turkey that both governments reduce military spending by 25%, but the proposal remained unanswered.

The lack of gender disaggregated data, gender impact assessments and gender-sensitive budgeting makes it difficult to carry out a comprehensive analysis of the proposed alternatives and make gender equitable recommendations. Greek feminists need to demand improved collection of data by the central and local governments, and the use of this data to inform budgeting and impact assessments.

Greece has a General Secretariat for Equality and a Centre for Gender Equality. These organizations used to be very active in promoting gender equality, but were weakened and downsized by the previous conservative administration. Feminists need to campaign for increased funding to these bodies and for more independence.